FIRST IT WAS insomnia. The patients streaming into the office of Pieter Cohen, M.D., all complained of sleepless nights. One woman also had headaches, chest pain, nausea, and fatigue. Another was depressed, sweating, trembling. Then a trucker showed up with yet another concern: He couldn’t figure out why he’d just tested positive for amphetamines.

It was 2006, and Dr. Cohen, working at a community health clinic in Somerville, Massachusetts, realized he had a medical mystery on his hands. Many of his patients are Brazilian immigrants, so Dr. Cohen, who speaks some Portuguese, began to ask more questions. Nothing about anyone’s diet or exercise habits seemed surprising. But when their lab tests started coming back, he was shocked. A number of the patients had amphetamines in their system, though none said they took any. Some also showed traces of known tranquilizers, hypnotics, and antidepressants.

Eventually, staff members at the clinic suggested a possible culprit. Brazilian-made diet pills, which came in different sizes and a range of colors (brown, red, white, and green) were being sold in generic packaging around the neighborhood. Dr. Cohen asked his patients directly about the pills, and they all admitted to taking them. “Because people were having such significant symptoms, it just gave me the sense that something powerful was in the pills that was mysterious or interesting,” he says.

He got samples from his patients and found a lab that could analyze them. It turned out that the pills contained dangerous amounts of fenproporex, an amphetamine derivative not approved for marketing in the U. S. and linked to anxiety, abuse, and dependence. The supplement had been spiked, a practice in which manufacturers cut corners and deceive customers by including harmful or even deadly ingredients in their formulas.

Dr. Cohen figured the next step was simple: He alerted his regional FDA office, hoping to see the pills taken off the market, but then . . . nothing. No warnings were issued, no recalls enacted. After several months, the pills were still on neighborhood shelves. Undeterred, Dr. Cohen wrote about his findings in two medical publications—the Journal of General Internal Medicine and TheAmerican Journal on Addictions. He created warning pamphlets and shared them in the community through local churches, and he talked to local radio stations and newspapers.

Once one of the main newspapers in São Paulo picked up the story, the pills started disappearing, probably because Brazilian authorities got involved. Dr. Cohen isn’t sure exactly what happened, he says, “but the timing was a nice coincidence.”

What he never imagined was that this probe might lead him to investigate another toxic supplement, then another, until his self-appointed role of policing the unregulated world of supplements turned into an obsessive quest. He now regularly analyzes dozens of pills and powders every year, pursuing any hunch that some dangerous ingredient might be lurking beneath a too-good-to-be-true marketing claim.

Adverse events related to dietary supplements cause an estimated 23,000 emergency-room visits a year in the U. S. Over an eight-year period starting in the mid-aughts, more than 200 shady products were taken off store shelves, according to an analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine. And it’s getting worse: Harvard researchers recently found that dietary supplements that claim to build muscle, sustain energy, or help with weight loss were linked to nearly three times as many severe medical events in people 25 and under as vitamins alone.

Never mind that millions of Americans spend billions of dollars every year on supplements without a guarantee of even minimal effectiveness. “Consumers in America have the sense that the FDA is quietly behind the scenes, ensuring that these products are safe,” Dr. Cohen says. “That’s the furthest thing from the truth.”

So he has stepped in where he sees the FDA failing, becoming a toxic-supplement hunter, bent on getting unsafe and mislabeled products off the shelves. “He’s a leader in the field,” says Patricia Deuster, Ph.D., the director of the Consortium for Health and Military Performance at the Department of Defense’s Uniformed Services University, who studies supplements and has coauthored papers with Dr. Cohen. “He can really be out there in front, criticizing” as an independent researcher not funded by a company or employed by the government, she says.

But being a solo sleuth and taking on both the multibillion-dollar supplement industry and the U. S. government is not without its risks. “I think some people were probably like, ‘Pieter’s crazy,’ ” Dr. Cohen says. “But to me, it’s fundamental to the work; it’s an extension of caring for the patients. Consumers are being harmed, and we need to do something about it.”

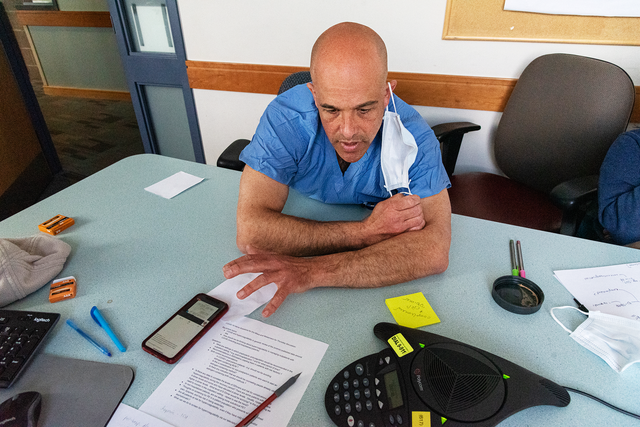

TALL, BALD, AND FIT, Dr. Cohen is 51 years old and wears beat-up sneakers with his scrubs. When talking about supplements, he becomes loud and animated, laughing incredulously about all the absurdities he’s discovered. When he’s with patients, however, he is calmer and carefully inquisitive. I visited him on a recent day during the Covid era, and he’d added an unusual piece of equipment to maximize that good bedside manner: Instead of a face mask, he sported an air-purifying respirator, basically a hood with a clear face shield, so that patients could read his lips and see his facial expressions.

Dr. Cohen grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, an affluent suburb of Boston, the son of a lawyer and state superior-court judge (his mom) and a professor of experimental psychology (his dad). In the late ’80s, he enrolled at the University of Virginia, thinking he might become an ecologist. While studying in Brazil, he ventured into the Amazon rainforest, where he met a family that had to sell its beloved, ecologically important mahogany tree to pay for an appendectomy. Another stint in the country followed, during which he did public-health research before heading to medical school to help more underserved communities. “I had all this privilege,” he says, “and I wanted

to make sure I gave back.”

Dr. Cohen did his residency at the same Somerville clinic where he works today, a part of the Harvard Medical School–affiliated community health network, Cambridge Health Alliance. His journey into the supplement world deepened after he discovered the local diet-pill problem and began working to publicize it. One day his phone rang; on the other end was a lawyer at the FDA’s enforcement office, who sounded just as frustrated as Dr. Cohen. The lawyer told him, “What you’re seeing in Somerville is what we’re seeing nationally” in terms of weight-loss supplements being spiked with drugs, Dr. Cohen says. And it wasn’t just Brazilian diet pills; it was, potentially, everything from brain boosters to protein powders to vitamins on the shelves at bodegas, nutrition stores, and drugstores.

Because many different manufacturers make these products, issuing a recall or seizing them directly from companies can feel like playing whack-a-mixture. “A lot of people would be like, ‘That’s not my lane—let the lawyers or the public-health experts figure that out,’ ” Dr. Cohen says. Instead, he started studying chemical structures, read about the history of the FDA, and came to recognize some serious problems in the regulatory practices for supplements, which he called out in The New England Journal of Medicine as a game of “American Roulette.”

The extremely loose rules of that game—or how supplements fit into the FDA’s regulatory framework—weren’t formally outlined until the 1990s, when, with bodybuilding and diet supplements gaining in popularity, Congress considered legislation reining in supplement makers. The industry objected with a well-financed campaign, including a TV commercial showing an armed squad seizing vitamin C from Mel Gibson, and in 1994, Congress passed an act governing supplements that even one of its architects now says is faulty.

The FDA’s definition of a supplement is any substance that contains a vitamin, mineral, amino acid, herb, or botanical that can be used to supplement the diet. The FDA has no power to approve most supplements before they hit the market and little recourse to stop distribution afterward. Look closely and you’ll see that nearly every product has a generic disclaimer saying that it has not been formally evaluated by the FDA. As a result, while some products contain exactly what’s listed on the label, others may manipulate their ingredients to cut costs or seem miraculously effective. The first clue that something is wrong may come only after people have gotten sick.

When the law was passed, there were about 4,000 supplements on the market. Now there are between 50,000 and north of 80,000. Last year, the FDA issued only 49 warning letters alerting manufacturers about suspect products. Meanwhile, the global supplement market grew to $140 billion in 2020 and is expected to keep expanding fast.

WHEN THE FDA does step in, its slow response has proved problematic. Consider the amphetamine derivative called DMAA, which is associated with heart attacks, seizures, and neurological problems. In 2011, when two soldiers who died while exercising were found to be taking workout supplements spiked with the substance, the DOD banned the sale of products containing this ingredient from its on-base stores. It also released a warning about the dangers linked to DMAA-containing products. By April 2013, the FDA had received 86 reports of people harmed by them. It issued a consumer alert and, soon after, stopped the manufacturer from distributing some of the products. Until then, it had only sent the manufacturer warning letters.

After 29 patients in Hawaii suffered liver damage, many after taking OxyElite Pro, one of the DMAA-containing weight-loss and performance-enhancing supplements, the state’s department of health acted to remove the product from stores.

Dr. Cohen’s goal is to speed up that whole process, to spur either the FDA or some other governmental agency to act at the first sign of trouble, before anyone else gets hurt. To do so, he’s developed his own network of doctors, academics, and doping experts who share tips about what emerging product ingredients might be harmful, and he recruits nonprofit and academic labs willing to analyze samples. Over the past decade, this small pharma Rebel Alliance has turned up an endless array of pills, powders, and botanical products containing things like banned stimulants, alternate versions of dangerous stimulants, ingredients with adverse effects at high doses, and drugs that were unapproved in the U. S.

Case in point: In 2013, a source tipped Dr. Cohen off that athletes using a popular workout powder called Craze were testing positive for an unknown amphetamine. The previous year, the product had been named the “New Supplement of the Year” by Bodybuilding.com, and it was being sold in stores and through online retailers. When Dr. Cohen bought and tested it, he identified a chemical called DEPEA, which is similar to meth. (This was not, as the label claimed, dendrobium orchid extract.)

Craze was manufactured by a Long Island–based company called Driven Sports, whose owner, Matt Cahill, had run other questionable supplement companies and already been sentenced for mail fraud and shipping mislabeled drugs to customers. In 2004, he also developed a muscle-building product that sparked customer reports of liver damage.

Rather than wait for the FDA to act, Dr. Cohen published his findings and shared the story with news outlets, including The Boston Globe, CBS News, and ABC News. That same week, Craze’s manufacturer announced it had ceased production due to safety concerns, well ahead of any FDA warning being issued. The product was discontinued, creating a new kind of playbook to help Dr. Cohen protect consumers.

In recent years, he has followed up on tips that led to similar success at identifying both an amphetamine variant called BMPEA in several weight-loss supplements and an unapproved neurologic drug called picamilon in supposedly memory-boosting products. As his public-awareness crusade has grown, he’s found that more states are willing to use his information to take action ahead of the FDA and target stores directly. After Dr. Cohen’s reports on BMPEA and picamilon were released, Oregon’s attorney general sued GNC and the Vitamin Shoppe for selling products with the ingredients, and the state of Nebraska filed a similar suit against the Vitamin Shoppe.

The Vitamin Shoppe reached an agreement with the Nebraska attorney general to no longer sell products that contain BMPEA. It settled the Oregon suit by agreeing to pay a roughly half-million-dollar fine and pulling the products with the substances that Dr. Cohen pinpointed from some store shelves. It also agreed to immediately suspend sales of anything with an FDA warning or advisory and investigate the safety of those products itself. In 2015, GNC said that it had stopped selling picamilon and BMPEA products, too, though it publicly announced that the FDA had not, at that point, raised safety concerns about those ingredients.

GNC now claims that all products it sells must meet specific standards for purity and strength. (The company did not respond to Men’s Health’s request for more information.) A spokesperson for the Vitamin Shoppe says that vendors must assure the retailer that their products “comply with all applicable laws,” and all products are reviewed by its scientific and regulatory affairs team before being sold. Its store-brand products are also analyzed internally to make sure they meet the expected level of purity and potency.

Even Amazon, an emerging force in the retail-supplement world, says it has “proactive measures in place to prevent suspicious, noncompliant, or prohibited products from being listed, and we continuously monitor the products sold in our stores.” Amazon requires companies to share a certificate of analysis (testing confirming the makeup of a product).

Dr. Cohen says even though some stores and chains are taking steps to ensure the safety of supplements amid serious shortcomings in the laws, smaller shops and Internet sites will continue fueling the problem. With companies now seeking more formal guidance, he’d like the FDA to issue rulings more quickly, but that hasn’t happened. Three years ago, California’s Department of Public Health noted that of about 750 supplements the FDA listed as “adulterated,” it had issued voluntary recalls for fewer than half. “They’re simply not doing their job,” he says of the agency.

The FDA has a more diplomatic stance. “We appreciate stakeholder interaction like this for raising awareness and bringing needed attention to these matters,” a spokesperson says. “We look forward to collaborating . . . to help ensure that products marketed as dietary supplements are safe, well-manufactured, and accurately labeled while preserving the original commitment to consumer access.”

DR. COHEN HAS reproached the FDA about its lack of effectiveness for years—but he never expected that he’d have to defend his own tactics in court. The problem started in 2014 after he read a study written by FDA scientists about supplements that purported to contain Acacia rigidula, a Texas shrub that had become popular on weight-loss products’ labels.

FDA scientists tested 21 products claiming to have the Acacia ingredient and found that nine of them instead contained synthetic material that turned out to be BMPEA. However, the agency didn’t list which supplements had the dangerous ingredient. Dr. Cohen waited, figuring it would at least issue warning letters to those manufacturers. That didn’t come to pass.

One of Dr. Cohen’s biggest frustrations is that even when the FDA knows about sketchy products, it often doesn’t give consumers useful information about them. “When the months were passing and nothing was happening, honestly, I couldn’t believe it,” he says. So Dr. Cohen ran similar research, and in 2015 he published a study finding BMPEA in several supplements for weight loss, sports, or cognitive function. He listed the names of the products and their manufacturers, as he likes to do: It makes his research replicable and gives consumers solid information on what to avoid. A trio of senators—Dick Durbin of Illinois, Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, and Chuck Schumer of New York—became aware of the study after it was published and started making news, and they pushed the FDA to act.

This time, the agency quickly sent warning letters to five companies telling them to “immediately cease distribution.” But it wasn’t just the government that noticed the paper.

That April, one of the companies Dr. Cohen cited, Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals, sued him for $50 million in compensatory damages as well as $150 million for slander and libel for publishing, then publicizing in news outlets, his findings about Hi-Tech’s supplements. The issue wasn’t whether some of its products included BMPEA; Hi-Tech admitted in the lawsuit that they did. Rather, Hi-Tech fought his statements that BMPEA was dangerous, hadn’t been rigorously tested in humans, and wasn’t derived from the natural Acacia rigidula source.

Despite the bankruptcy level of damages attached, Dr. Cohen wasn’t concerned at first. “I was naively thinking, at the time, that truthful speech is 100 percent protected in America,” he says. It wasn’t that simple: The case still had to go to trial.

The good news? Harvard defended him, covering the costs of the lawyers. The bad news was everything else. In discovery, a phase of litigation in which both sides seek evidence, Dr. Cohen had to dig through his emails to find anything related to this study and hand it over to Hi-Tech. Then he had to reread and analyze all those communications in case he was asked about them in his deposition or at trial.

It got so all-consuming that in the early mornings, before his wife and three kids were up, or over the weekends at his kids’ sports practices, just about the only thing Dr. Cohen did was recheck his own work. “I spent every free moment I had,” he says. After a six-day trial, during which he argued that his speech was scientific opinion, protected by the First Amendment, and about a matter of public concern, the jury found in his favor.

Hi-Tech’s CEO and lawyers did not respond to requests for comment, and while some of its brand names that Dr. Cohen analyzed are still available, it’s unclear whether the company has altered the supplements’ makeup. As for Dr. Cohen’s case, it was a win but one unlikely to encourage other independent investigators. “The degree of scrutiny that his work was put under is something that, honestly, I think very few academics would like to go through,” says Dan Levy, Ph.D., a professor of public policy at Harvard and a friend of Dr. Cohen’s.

For Dr. Cohen, the trial had a single upside: His work was having enough of an effect that a company tried to stop him. “I definitely didn’t want to have research that is just sitting there and never read,” he says. “I want to have a positive impact on health.” He went right back to his research and to calling out brand names and companies.

IN SPITE OF the continuing threat of lawsuits, Dr. Cohen has not slowed down. He’s now published more than 50 academic papers, many skewering major manufacturers for being less than forthright, and in many cases downright fraudulent, about their products and promises. He’s made stores more accountable for what they’re carrying by giving state regulators actionable information to get ahead of problems, even if the FDA is slow to take measures.

Dr. Cohen paused these investigations when the global pandemic hit, as he put all his energy into sharing anything that might be helpful for doctors trying to diagnose and treat Covid. This past March, for the first time since the pandemic began, Dr. Cohen published a new study, looking at 17 sports and weight-loss supplements with labels that listed deterenol, a stimulant that can cause sweating, nausea, and cardiac arrest, as an ingredient.

Deterenol has never been approved for humans in the U. S. In 2004, the FDA determined that it is not permitted as a dietary ingredient in supplements. That some brands advertise it explicitly or use scientific synonyms, Dr. Cohen says, is a classic example of just how openly manufacturers flout FDA rules. Four of the supplements he tested didn’t contain the prohibited substance at all, despite the claim that they did; all the others contained it or had cocktails of deterenol with other stimulants. “It’s dizzying how complicated these products are,” he says, “which is incredibly frustrating from the perspective of the FDA not doing its job.”

In the meantime, plainly hyperbolic online reviews of some of these products suggest how strong they might be. Of Chaos and Pain’s Cannibal Ferox Pre Workout, one reviewer wrote, “This stuff is just a few levels below cocaine . . . . I can smell colors.” Of Psycho Pharma’s Edge of Insanity Pre Workout, a reviewer said, “As I like to call it, edge of a heart attack.” That’s a little different from the brand’s promise of “Exploding Muscle Pumps, Zen Energy, Razor Focus” and “Psycho Endurance”—all printed in bold lettering on the front of each jug. (Neither Chaos and Pain nor Psycho Pharma responded to requests for comment.)

Either way, Dr. Cohen hopes the FDA or another governmental authority uses his latest round of intel to take these drugs off the market. At press time, the FDA had yet to act. “We appreciate studies like this for raising awareness and bringing needed attention to these matters,” an FDA spokesperson says. “However, in general, the FDA does not comment on specific studies but evaluates them as part of the body of evidence to further our understanding about a particular issue and assist in our mission to protect public health.”

Regardless, Dr. Cohen won’t stop sounding the alarm. He understands that the FDA is weak and its mandate woefully outdated. The real culprit, then, is Congress, for failing to create new laws that solve the problem. And whenever there’s a problem with Congress, it’s actually a problem concerning us—the people who hire our representatives to make laws in our name. So he plans to keep working, unpaid, even harder. “The better that people understand [the issues], the better the eventual law we might be able to have,” he says.

His next task: studying CBD products along with more traditional supplements. He’s also suggested a regulatory overhaul at the FDA, both in academic publications and on calls with congressional staff and consumer advocates. Earlier this year, the FDA requested legislation requiring that all supplements for sale be registered, which would give the agency a better handle on the market and the ability to act when dangerous or illegal ingredients are introduced.

Personally, Dr. Cohen doesn’t even take a multivitamin. “My take is just: It’s best to go with exercise and healthy food, and you have to have pretty strong evidence to convince me that something is better than that,” he says. But he did make a small concession at home: When his 19-year-old son got interested in supplements and his 15-year-old son started watching TikToks on pre-workout regimens, he let one of them try protein powders. Now, though, they stick to healthy diets—not sports supplements.

He understands the pressure that comes with comparing yourself with others, and how anyone who has lost a step or wants to stay one step ahead might go searching for an edge. So Dr. Cohen continues to research and write and pitch and advocate, trying to get a single message to consumers of supplements: Buyer beware.

The MH Guide to Safer Supplement Shopping

Products that promise bigger muscles, increased energy, and weight loss are among the most commonly spiked. Even if you’re just buying vitamins, here are three tips from Dr. Cohen to make sure you’re getting what should be in the bottle.

- Stick to well-studied ingredients like protein, amino acids, and creatine. When in doubt, check the USADA’s high-risk list and the DOD’s supplement-safety program.

- Avoid bold claims. Go for “protein powder,” not a “muscle builder,” or “ginkgo,” not a “memory enhancer.”

- Look for third-party certifications of independent testing from places like USP, ConsumerLab.com, and NSF International.

This story appears in the July 2021 issue of Men's Health

Stephanie Clifford is an award-winning journalist writing about criminal justice and business, and author of the bestselling novel Everybody Rise.